Blog » Kaboom: an unusual Minesweeper

Kaboom: an unusual Minesweeper

This is a post about development of Kaboom, a Minesweeper clone with a twist.

Apparently Minesweeper has a pretty long history for a computer game, but I guess most people remember the versions bundled with Windows. I was never good at Minesweeper but I enjoy a game from time to time. Some people play more seriously, see for yourself if you want to enter that rabbit hole.

And if you just want to get in the mood, go watch Minesweeper - The Movie.

The idea

Recently, I had an idea: what if you had to play Minesweeper against the computer?

Normally, the arrangement of mines is decided at the start of the game (except for some trickery so that you cannot lose on the first click). But what if there was no pre-determined arrangement, and the game was allowed to choose after you play?

It could be quite cruel: if you are playing on a square that could contain a mine, it would always contain one! So the you have to always prove the square is safe.

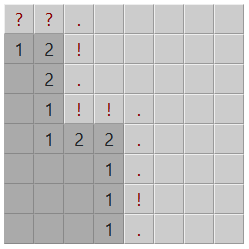

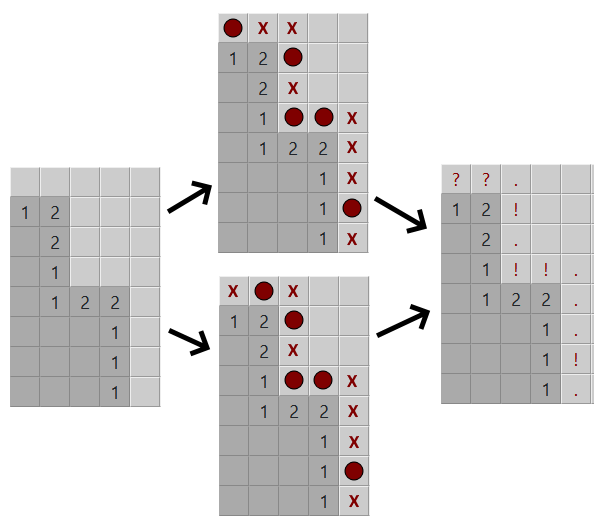

(On the above board, the squares marked with . are guaranteed not to contain a mine, and the squares marked ! are guaranteed to contain one. The question marks are uncertain: maybe if you reveal more squares, you can deduce something about them.)

On the other hand, there are situations where you are forced to guess:

One of the bottom squares contain a mine, but it's impossible to say which one. You have to select one of them. But according to what I just said, that would mean certain death! I wanted the game to be cruel, but now it's unwinnable.

So I'll modify the idea a bit and say you are allowed to guess, but only if there are no safe squares left. This way, the game will be cruel, but fair.

In other words:

- If you play a square that is guaranteed safe, it's empty.

- If you play a square that has a guaranteed mine, it will contain a mine and you will blow up.

- If you play a square that is uncertain, then:

- If there are any safe squares on the board, you are punished for guessing and that square will contain a mine.

- Otherwise, guessing is allowed and that square will be empty.

Mines at the boundary

How to implement such a game? I could try computing all possible boards, but that doesn't sound realistic: even a small 10x10 board means 2^100 possibilities. Selecting just the ones that contain exactly N mines doesn't help us much.

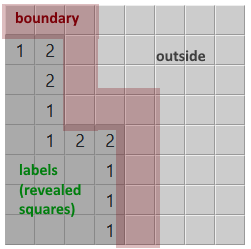

Fortunately, I don't have to care about the whole board. We don't known anything about mines not adjacent to labels. I just care about the ones at the boundary, the rest could be determined completely randomly.

Then, I can compute all possible arrangements of mines at the boundary, consistent with the labels. Backtracking is a good technique that will brute-force all combinations but also quickly back out as soon as we determine a branch of computation is impossible.

Above, there are 2 possible arrangements of mines on the boundary. By combining them, we know which squares are guaranteed to be empty or full.

I also need to track total number of mines. So the arrangements are really like "5 mines at the boundary, 5 mines remaining on the outside". This is important because otherwise I might generate too many mines on the boundary (or too few!)

So, I have all possibilities. What happens when the user chooses to reveal a square?

- Select a random possibility (but one that satisfies the "cruel, but fair" rules). This will determine mines at the boundary.

- Randomly scatter the remaining outside of the boundary.

- If the selected square contains a mine, game over.

- Otherwise:

- Compute the new label for revealed square

- Reveal additional squares if it happens to be a 0

- Forget the possibility we selected earlier! Only the labels will be binding from now on.

This is very inefficient

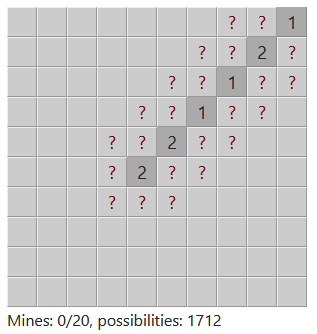

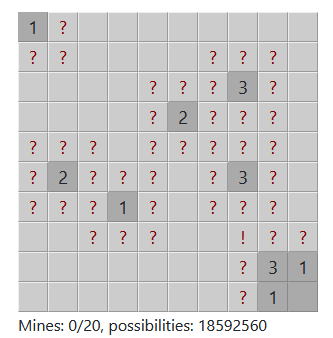

For smaller boards, this is OK. Usually there is only a few possible combinations… hang on, what is this?

Oh no.

Somehow I managed to unlock 18 million possible mine arrangements. My Firefox is taking up 12 gigabytes of memory and revealing a square takes half a minute. Clearly, I need a better algorithm.

You might say that since Minesweeper is NP-complete, I cannot escape exponential running times. And that's true in the general case, there will be "evil" positions that take a lot of time to compute. But most of the time, for random positions and a small board, I can do much better than traversing millions of possibilities.

I don't need to store all the combinations. I don't even need to compute all the combinations. What I need is a way to:

- check if a given square is guaranteed safe, guaranteed dangerous, or uncertain,

- find any valid possibility (possibly with additional requirement that a given square is empty, or full).

And if you look at the screenshots, there are many clusters of ? ? ?, but they are possibly independent of each other. Maybe I can reason about parts of the board in isolation. In fact, there are already tools for automated reasoning that implement all kinds of clever tricks…

Finding a solver

Instead of implementing the clever tricks myself, I am going to use a SAT solver. These are tools that take a formula consisting of boolean variables, and search for a set of values that would make the formula true. Which is more or less what we need here.

A more powerful class of software is SMT solvers which operate on richer set of values and formulas, such as first-order logic (quantifiers), arrays, integers and so on. It would certainly help to at least be able to specify some equations on integer numbers. However, I am looking for something working in a browser. People managed to port sophisticated tools like the Z3 prover to browser, but the WebAssembly version is a 17 MB download and that sounds like an overkill here.

So I found MiniSat, a small SAT solver, that has been compiled to Javascript by Joel Galenson. The compiled file is just 200 kilobytes so I'm going to go ahead and grab it.

CNF formulas

SAT solvers operate on conjunctive normal form (CNF) formulas. A CNF formula is "an AND of ORs", for example:

(a | ~b | ~c) & (c | d ~e) & f

You can convert any propositional logic formula (variables, and, or, not, implication) into CNF, so it's something like a universal format.

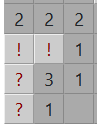

So how do we use it? Let's say we have a board:

? ? 1

2 ? 1

If I create variables for the unknown squares (clockwise: x1, x2, x3), they will need to satisfy these equations:

x1 + x2 + x3 = 2

x2 + x3 = 1

x2 + x3 = 1 (same as previous)

But how to express "a sum of variables is 2" in CNF?

I figured out a way, which I learned later is called "binomial encoding" and is the most straightforward encoding people use. You need to consider all possible subsets of variables. For example, for x1 + x2 + x3 = 2, you need the following formulas:

- For every subset of 2 variables, at least one is true. That ensures the sum is greater than 1.

(x1 | x2) & (x1 | x3) & (x2 | x3)

- At least one variable is false. That ensures the sum is less than 3.

(~x1 | ~x2 | ~x3)

For x2 + x3 = 1, I need a similar set of formulas:

- At least one of the variables is true:

(x2 | x3) - At least one of the variables is false

(~x2 | ~x3).

Putting it together, I will have a CNF formula with 6 clauses (parts). In the standard DIMACS format:

p cnf 3 6

1 2 0

1 3 0

2 3 0

-1 -2 -3 0

2 3 0

-2 -3 0

The clauses are all terminated by 0, and negation is marked with a minus. If I plug it into MiniSat (try that for yourself), I'll get:

SAT 1 2 -3

That means that MiniSat found a solution where x1 and x2 are true, and x3 is false. Here is how the board would look like:

! ! 1

2 . 1

The whole program is a bit more complicated than that: this is just a single solution, another one exists. So in order to find out whether x1, x2, x3 can ever be true (or false), I need to make more queries. I need to ask "given the above formula and also x1, is it satisfiable? what about the above formula and also ~x1"?

The encoding means that I need to find all possible combinations (e.g. all subsets of 3) of a set of variables. However, for a given equation there will be only up to 8 variables, and so the formula is usually small enough for MiniSat to solve quickly.

Keeping track of number of mines

Unfortunately, that is not a complete solution! I still need to track how many mines are left. Some combinations should be impossible, because otherwise you can generate more mines than is allowed and the game will become unwinnable.

In fact, the opposite case is also possible: if an arrangement contains too few possible mines, the game will crash because there will be no place left to put the extra ones.

So I need to specify in the SAT formula that "the number of mines is at least X and at most Y". Initially, I thought I could just use the earlier trick with all combinations. Unfortunately it doesn't work too well with larger numbers. If there are, say, 20 squares and 10 mines, then after plugging the numbers into binomial coefficient we'll find out the number of combinations is already into 6 digits!

This is when I learned there are many many other ways of encoding the sum of variables as a SAT formula. You need to create a circuit that will combine the individual variables. See for instance this StackExchange answer or this one.

I ended up implementing the one from a paper called Efficient CNF encoding of Boolean cardinality constraints, by Olivier Bailleux and Yacine Boufkhad. It's a tree that recursively adds unary numbers (or, depending on how you look at it, sorts the bits so that all ones are at the beginning):

At the end of this circuit, you get a sorted set of "output" variables. To assert that the sum is at least X, check that first X output variables are 1. To assert that the sum is at most Y, check than the last N - Y output variables are 0.

Unfortunately, while much better than using all possible combinations, this circuit is still pretty wasteful as it generates Ө(N^2) clauses. When the number of open squares is around 100, the game becomes sluggish. We can still optimize.

Reducing the number of queries

After implementing all of that, I noticed I could still reduce the number of queries to the solver. I wanted to determine the status of all the squares (i.e. check if they are guaranteed dangerous, guaranteed safe, or neither). I did that using a simple loop. Let's say the board is described using a formula F:

- Solve for

F & ~x1to check ifx1can ever be 0 - Solve for

F & x1to check ifx1can ever be 1 - Solve for

F & ~x2to check ifx2can ever be 0 - Solve for

F & x2to check ifx2can ever be 1 - and so on.

What I noticed is that if I do get a solution for F & ~x1, the solution will contain assignments of all the other variables as well. This already answers many other questions: if the solution contains x2 = 0, I don't need to ask if x2 can ever be 0 because I already know that. (If I don't get a solution for a given query, well, it doesn't give me any extra information). This allows me to reduce the number of queries by about 2 to 5 times, depending on the arrangement.

Caching

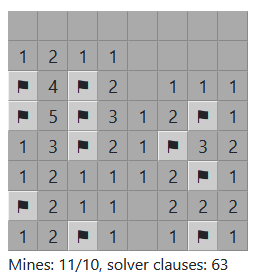

This still doesn't solve the problem of a huge formula generated by the "counter" circuit. As I said before, the number of clauses is on the order of N^2. On a big board, the formula can be as big as 10,000 clauses.

Fortunately, most of the time we know many fields for certain. If a field is guaranteed empty, or guaranteed full, it will never change! That means we can cache its value and not include it in the SAT formula. Once we determine a status of a field, we don't ever need to include it in calculation again. Only the uncertain fields (?) will be kept as long as they are uncertain.

This optimization is a bit scary: we no longer have a formula stating the correctness of the entire board. If everything else works as planned, that's not a problem, but it might make bugs harder to track.

Another corner case: playing outside

Should you be allowed to click anywhere on the map, outside of boundary?

Initially I thought that it should be treated the same as guessing: if there are no safe squares, you can just click anywhere on the board. But some friends thought it was weird that it would guarantee you an empty spot anywhere.

So I changed it so that clicking outside is always punished (as long as the game has not run out of bombs to punish you, that is). With the exception of game start, of course, because then the whole board is "outside".

But it turns out that there is another corner case related to that: what if all your boundary fields are deadly?

3 . .

. . .

. . .

You have no choice but to reveal something else. This case could make the game unwinnable right at the start. So now there is another exception. You are allowed to play outside of boundary when:

- nothing is revealed yet, or

- all bombs in the game can be proven to be on boundary (clicking outside must be safe), or

- all fields on the are certain to have bombs (you are forced to click outside).

Update: The change turned out to be controversial, as the restriction is somewhat artificial. I added a switch that will allow/disallow outside guesses.

That's all

You can play Kaboom here. Try enabling the debug mode: it makes the game trivial, but shows well how it works underneath.

The source code is at Github. It's not very pretty.

You might be also interested in a related minesweeper game by Simon Tatham, the creator of PuTTY. His version has a different twist: it's always solvable without guessing.